A Little Silk Road History

A perilous network of paths that flourished from around 200 BC until the Middle Ages, the Silk Road stretched more than 7,000 miles from east to west, a meandering skein of trails that formed one of the most transformative super-highways in human history. The Silk Road was the prototype for globalization and shaped the modern world: not only did it bring silk to the West, but it gave us printing, spices, equine harness, gunpowder, crossbows, rhubarb, the mechanical clock, spinning wheels, jade, rubies, wheelbarrows, paper, pasta and so much more. Its history is the story of mighty emperors, brave adventurers, merchants and missionaries, all of whom created a network of commerce that linked tens of millions of lives as far away as Africa and Southeast Asia.

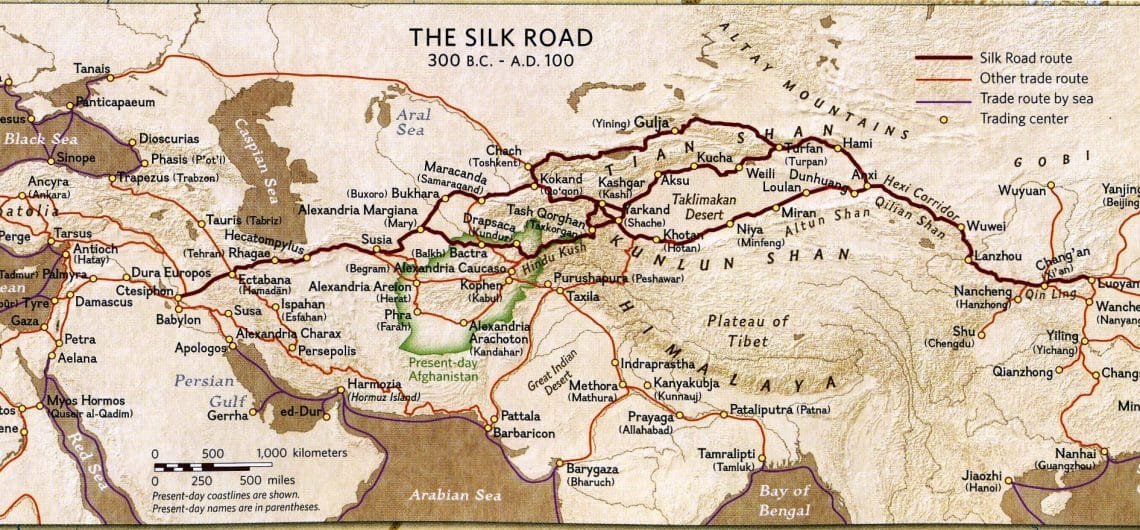

The Silk Road (a term coined by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in the late 19th century) was by no means a single road, but a complex network of trade routes, both terrestrial and maritime, which connected the Mediterranean to China through Central Asia and the Middle East. While people had begun using sections of these trading routes as early as 3000 BC, the author Peter Frankopan writes that: ‘Two millennia ago, silks made by hand in China were being worn in the Mediterranean, while pottery manufactured in France could be found in England and the Persian Gulf. Spices and condiments grown in India were being used in the kitchens of Xinjiang, as they were in Rome. Buildings in Afghanistan carried inscriptions in Greek, while horses from Central Asia were being ridden proudly thousands of miles away to the East…The ancient world was much more connected and sophisticated than we think. A belt of towns formed a chain spanning Central Asia. The west had begun to look east, and the east had begun to look west.’

Two things provided vital momentum in the creation and development of these pan-continental networks: silk and horses. While the Chinese had the precious secret of sericulture, the Central Asian nomads at their western borders had horses – essential for war. Wanting to get his hands on some of these valuable creatures, in 138 BC the Chinese emperor sent Zhang Qian, a young officer of the emperor’s palace guard, to lead a diplomatic mission to the west and bring back some horses. In this and other subsequent adventures (which included a spell of imprisonment) our hero Zhang Qian learned a great deal about the mysterious lands to the west. Most importantly, in what is now Uzbekistan’s Fergana Valley, he found a large, strong breed of horse that would be ideal for Chinese military needs.

Soon the Chinese were trading silk for thousands of these large Central Asian mounts – so called ‘Heavenly Horses’ that were described by Chinese writers as being sired by dragons and sweating blood. A first-century B.C. poem, part of the chronicle of China’s history, The Shiji, marks the arrival of the first of these steeds:

The heavenly horses arrive from the Western frontier,

Having travelled 10,000 li, they come with great virtue.

With loyal spirit, they defeat foreign nations

And crossing the deserts, all barbarians succumb in their wake!

In time this trade would plug China into the lucrative markets of the West, including the booming Roman world. While this silk-for-horses trade didn’t arrive out of a vacuum, the Persian empire, nomadic movements and Alexander the Great had all helped lay the foundations, Zhang Qian’s remarkable adventures were important early steps in creating the Silk Road.

As east-west trade developed, the routes fanned out across the whole of the Eurasian landmass. From desert oases on the western fringes of China trade flowed along three main routes. Two northern roads passed over the Pamir and Tien Shan mountains into Central Asia, while a third road went south via Khotan and Tashkurgan (towns in modern Xinjiang) into today’s Pakistan. This route skirted the Taklamakan Desert (meaning ‘He who goes in, never comes out’), where dangerous extremes of temperature and blinding sandstorms claimed the lives of many a Silk Road traveller. Beyond that, the pathways probed into the mountains of India and Afghanistan, across the deserts of Central Asia and Iran, around the Caspian Sea and over the Anatolian plains. Once they reached Mediterranean ports, the goods were shipped on to Rome.

Great cities rose and fell along the route – Samarkand, Khiva, Bukhara, Merv, Mary, Tyre, Antioch, Palmyra, Baghdad – and canny middlemen like the Sogdians accumulated vast wealth. Indeed, the Sogdians, whose language was the lingua franca of the Silk Road, were said to feed their babies honey so as to sweeten their tongues for future trade.

But it wasn’t just material goods that travelled along these paths. The Silk Road also allowed for the spread of ideas – both in terms of scientific and engineering techniques – and religions. During the 1st century AD Buddhism was carried from Northern India along trade routes. Christianity was able to expand in the same way. Moreover, as religions came into contact with one another, they began to borrow ideas, a phenomenon known as syncretism. It is striking, for example, that a halo became a common symbol across Hindu, Buddhist, Zoroastrian and Christian art.

The most devastating thing ever traded on the Silk Road, however, was disease. The bacterium Yersinia pestis, carried on fleas which attached themselves to Central Asian rats, came westwards in the years 534, 715 and, most devastatingly, in 1346, when the Black Death killed approximately 40 per cent of the population of Europe.

Various theories have been posited regarding the decline of the Silk Road, among them the fragmentation of Central Europe following the end of the Mongol Empire, and the fall of Constantinople in 1543. But the main reason is Columbus’ discovery of the New World in 1492 – an expedition that transformed Western Europe from a regional backwater into the world’s political and economic centre of gravity. Around the same time, Vasco de Gama became the first to sail around Africa into the Indian Ocean and thus made it possible to establish naval trade routes between Europe and Asia. These marine pathways became direct alternatives to the traditional Silk Road trade routes, not subject to taxation and brigandry on the long road from east to west. With Europe now at the centre of a global communication, transportation and trade system, the heyday of the Silk Road had come to an end.

Today the countries at the heart of the Silk Road are once again rising to the fore, with more and more people showing interest in this fascinating and long-overlooked region. To travel here is to follow in the footsteps of historical legends such as Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, Marco Polo and Tamerlane, not to mention the countless merchants, monks, soldiers and pilgrims who walked, marched, prayed, lived and died along these routes.

A Short History of Silk

Soft, strong and alluring – silk was first produced in China. According to Chinese legend the secret of silk goes back to the Yellow Empress of China. ‘The lady of the silkworms’, as she’s otherwise known, was pondering life under a mulberry tree one fine day in 2700 BC when a silkworm cocoon fell into her tea and began to unravel into a long, silken thread. Realising this was something rather special, the clever Empress went on to invent both sericulture and the loom.

Archaeological finds suggest that the origins of sericulture were even earlier than this, but whatever the truth, what’s certain is that the Chinese fiercely guarded the secret of sericulture for thousands of years, condemning to death anyone who tried to smuggle silkworms or their eggs out of the Empire. Indeed, the secret was so well kept that as late as 70 AD the Roman historian Pliny wrote that “Silk was obtained by removing the down from the leaves with the help of water…”.

China’s closely guarded secret became a source of huge wealth. And it was the Romans, who’d developed a lustful, complicated relationship with this mysterious fabric, who drove this trade the most. Romans had first encountered silk at the ill-fated Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, when their troops were cowed by the spectacle of the Parthians’ colourful banners, woven from Chinese silk. The Roman second-century historian Florus later described the moment when the Parthian generals “displayed all around [the Romans] their standards, fluttering with . . . silken pennons” before describing how the army was slaughtered and its Roman commander killed.

A century after the route at Carrhae, silk was immensely popular across the fast-expanding Roman Empire. This weakness for a foreign luxury was bitterly criticized by Rome’s stern moralists. Seneca, writing in the 1st century AD, was horrified at the popularity of this sheer material, complaining that silk garments could barely be called clothing since they hid neither the curves nor the decency of ladies of Rome. Pliny the Elder, writing at a similar time, objected to the popularity of silk on financial grounds, resenting its high cost and inflated prices: the best Chinese bark (a particular kind of silk) cost as much as 300 denarii – a Roman soldier’s salary for an entire year. “At least a hundred million sesterces flow out of our empire every year to India, China, and Arabia. That is how much luxury and women cost us!” he complained.

As silk was causing an outburst of moral hand-wringing in Rome, in China it had become the main currency. By the time of the Han Dynasty (206 BC to 220 AD) farmers were paying their taxes in grain and silk and silk was being used for paying civil servants and rewarding subjects for outstanding services. Before long it began to be as a currency in trade with foreign countries (such as payment for the valuable Central Asian horses). So central was silk to Chinese life that 230 of the 5,000 most common characters of the mandarin “alphabet” have silk as their “key”.

Despite China’s efforts, the secrets of silk production did finally make their way west. In 440 AD a Chinese princess, betrothed to a ruler of Khotan in today’s Xinjiang, hid some silkworm eggs in her bridal headpiece and smuggled them west. A century later, two Nestorian monks appeared at the Byzantine Emperor Justinian’s court with silkworm eggs secreted in their hollow bamboo staves. By the sixth century the Persians had mastered the art of silk weaving, developing their own rich patterns and techniques, and by the 13th century—the time of the Second Crusades—silk production was widespread in Europe.

The Rise of Islam (and its impact on the Silk Road)

The spread of Islam had a huge impact on the Silk Road.

From its beginnings in a cave on Jabal al-Nour mountain near Mecca, where the Prophet Muhammed received his first revelation in 610 AD, Islam spread eastwards with remarkable speed. In the space of a century, Muslim armies had conquered the entire Arabian peninsula, much of North Africa and most of the Iberian peninsula, thus creating the largest empire history had ever seen.

By the start of the 8th century, this mighty new Caliphate had reached the western borders of China. In 751, the Arab army defeated the Chinese at the battle of Talas, in today’s Kyrgyzstan, allegedly capturing Chinese paper makers and bringing these skills to the west. Although this is hard to prove, it’s true that from the later part of the 8th century the availability of paper made the recording, sharing and dissemination of knowledge much faster and quicker.

With the rapid spread of Islam came a surge in the spread of ideas. Muslim scholars were hugely prolific, inventing or making significant contributions to algebra, trigonometry, optics, anatomy, astronomy, and medicine. As Peter Frankopan writes: ‘While the Muslim world delighted in innovation, progress and new ideas, much of Christian Europe withered in gloom, crippled by a lack of resources and a dearth of curiosity. Christianity was linked to a disdain for science and scholarship, with curiosity seen as ‘nothing more than a disease.’ ‘As one author wrote, when writing about the non-Islamic lands, ‘we did not enter them [in our book] because we see no use whatsoever in describing them.’’’

At the same time as 10th century Arabic scholars such as Al Biruni (from what is today western Uzbekistan) was establishing that the world revolved around the sun and rotate on an axis, Europe was languishing in academic darkness.

Although often overlooked, this ‘Lost Enlightenment’ was the precursor to the European Renaissance – without it, the intellectual flowering that happened in medieval Italy and elsewhere would likely not have happened.

The Present Day

After being at the centre of the world for more than two millennia, today Central Asia and the Caucasus – the heartlands of the Silk Road – remains in relative obscurity. Few people could name all the ‘Stans, or point them out on a map, and many wrinkle their faces in confusion on hearing their name. ‘Tajik-where?’ they say. ‘Where’s that?’

But things are changing. Fast. A quarter of a century after the fall of the Soviet Union, China’s grandiose, multi-billion dollar Belt & Road initiative is once again placing these countries at the heart of a new world order.

In 2015 the historian Peter Frankopan’s published, The Silk Roads: A New History of the World – a groundbreaking look at history written from the perspective of the countries at the heart of the Eurasian landmass. A runaway best-seller, the book has been number one in the UK, China and many other countries, and remained in the UK top ten for nine months in a row. Its success is indicative of surging interest in the region.

Travellers, more than ever, are looking for new, exciting destinations, places where they can unplug, unwind, escape from the hordes, breathe pure mountain air and experience genuine hospitality. And this part of the world offers exactly that. Tourists are flocking to Georgia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Iran, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan in ever greater numbers. Tajikistan was the second fastest growing tourism destination in the world in 2016, and almost every UK newspaper and travel magazine named one of the ‘Stans as a ‘Must Visit’ destination for 2018. 2.5 million tourists visited Samarkand, in Uzbekistan, alone last year. Now there could not be a better time to visit these exciting, engaging and fast-changing Silk Road countries.

A Significant Future?

Bruno Macaes’ recent book The Dawn of Eurasia is one example of a growing canon of literary work dedicated to the subject of the ‘New Silk Road.’

Since 2013, China’s much-vaunted $900 billion Belt and Road Initiative has captured global headlines for its reach, audacity and sheer scale of ambition. The longest rail service in the world is no longer the Trans-Siberian, but the Yiwu (China) to Madrid, and Chinese freight trains now travel all the way from Yiwu to the UK, terminating at writer Joseph Conrad’s home in Essex.

This is the New Silk Road – and the impact it will have on the western-centric view of our world will be profound. The historic Silk Road was about the movement of thought, religions and cultural mores as much as it was about trade. With three of the world’s largest economies forecast to be in China, India and Japan within a couple of decades, the balance of power and influence in the world is shifting, and it is these lands of the ancient Silk Road that are once again rising up.

The old caravanserai and camel trains are being replaced by modern skyscraper-clad cities, motorways and rail links that permit bullet trains to zip between the east and west. And the change is happening fast. We see it every year we spend time in Central Asia.

Central Asia is precisely that – central.

It is central to a global future, and those who don’t pay attention to the ripples emanating from the changes happening there are in denial. Make no mistake; the Silk Road is going to affect us all once more. Watch this space.

Characters of the Silk Road

Over the centuries, many people have been associated with the Silk Road. Among them were traders and merchants, missionaries and zealots, warlords and world leaders, scholars and writers.

A few of these characters have become forever associated with the Silk Road. Here you’ll find the stories of just a few such personalities.

-

A major step in the opening of the Silk Road between Eastern and Western civilisations occurred around 330 BC.

The then-leader of the Greek Empire, Alexander the Great, conquered Persia, taking control of all Persian roads and trade routes that allowed him to push deep into Central Asia with a well-trained army. He left a legacy of Greek influence that stood the test of time.

Alexander eventually married the daughter of a Bactrian chief in present-day Afghanistan. Her name was Roxanne, and the alliance saw Alexander building his eastern capital at Bactria in Northern Afghanistan. This forward base allowed Alexander to build around 30 cities across Central Asia, many filled with Greek art and architecture. Those cities include names we still know now, such as Merv, Kandahar, Termez, as well as countless others named after him (there are at least ten Alexandrias and Iskanders).

He died in Babylon aged just 32. Few humans have had the impact he managed to exert in such a short life.

-

You can’t truly learn about the Silk Road without hearing a bit about Chinggis – or Genghis – Khan.

This rogue not only united the disparate tribes of nomadic Mongol peoples into the Mongol Empire, but went on to create the biggest empire that has ever existed. Not bad for a boy called Temujin who grew-up watching the family’s herd of camels. He was spirited, even then, and by spirited we mean that he killed his own brother for stealing fish from the family.

By 1196 Temujin had become Chinggis Khan, an honorific title that probably meant ‘strong’ king in those days. There is much written elsewhere about Chinggis Khan, but whether he was the greatest ruling military mind or a genocidal lunatic, it cannot be argued that his impact on the Silk Road was anything other than deep and formative. It was he that brought the entire Silk Road under one political system for the first time (the Pax Mongolica), and his sons and heirs were not only incredibly formative in Central Asian history, but also the wider history of the world after the death of Chinggis himself.

The Mongol empire also permitted the transfer of Yersinia Pestis, or the Black Death, from the Central Asian steppes to the courts of Europe. It decimated the European population between 1347 to 1351, killing an estimated 200 million and changing the course of history forever.

It was Chinggis’ son Ogdei that expanded the Mongol Empire to the very gates of Europe (the Eurasian steppe actually ends on the shores of Lake Balaton in modern-day Hungary), and his Grandson Kublai Khan that was ruling at the time of Marco Polo’s travels. Amir Timur (better known as Tamerlane), related to Chinggis through his favourite wife, Bibi Khanum, was hugely formative among the Khanates of modern-day Uzbekistan and Tajikistan and has left a legacy that is retold to this day. Timur’s own descendant Babur was the first Emperor of the Mughal dynasty that ruled much of India, Pakistan and Afghanistan from 1526 to 1857.

That is quite an epic set of global impacts starting with a boy who looked after camels.

-

The best-known Silk Road traveller of them all was Marco Polo, born in Venice in 1254 AD to a family of silk merchants.

Marco’s uncle and father were reputedly the first Europeans to meet Kublai Khan, so young Marco had a significant introduction to the ways of exotic travel from an early age.

When Marco was seventeen he set out with his relatives towards China and after three years, a crossing of the High Pamir mountain range and a traverse of the Taklamakan Desert later, the Polo family reached the Emperor Kublai Khan as his capital Khanbaliq – today’s Beijing. The emperor asked the family to stay, which they did for seventeen years, with Marco becoming a trusted advisor to the Emperor.

This lavish lifestyle came crashing down on his return to Venice when the city went to war with nearby trading rival Genoa and he ended up in prison. But it was in prison that he met the writer who would pen the story of Marco’s adventures – then called “Description of the World”.

The first eyewitness account of the hidden lands of China, India and everything in-between, the book became famous across Europe. In it, he describes the Mongol Empire and the great cities of the Silk Road as well as the peoples and cultures he met along the way.

There is still conjecture about whether everything written was entirely truthful – for instance, he is criticised as a fake for not mentioning such Chinese cultural staples as chopsticks, tea or the ever-so-subtle Great Wall of China. Other scholars have made the counterpoint that he lived not with the Chinese but with the Mongol rulers, so his cultural history is true to them and not the Chinese. All in all, his observations have generally stood the test of time, and he remains a towering figure in the history of the Silk Road.

-

Moroccan scholar Ibn Battuta made his lengthy journey, aged only twenty, just fifty years after Marco Polo left home.

He set out from Tangiers on a hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca but in accordance with the words of the Prophet Muhammad – “seek knowledge, even as far as China” ringing in his ears, decided to keep going.

In fact, he kept going for twenty-nine years. He visited Africa, Europe and Asia, covering over 75,000 miles in total and later penning a snappily-titled book about his adventures: “A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling”. Thankfully it is more widely known as The Rhila, an Arabic term for a book about travel. He was a fascinating character, and if you get the chance to read about him, you’ll find him an insightful eye on the world at the time.